Knowledge Base

Large Language Model Overview

A Large Language Model (LLM) is a type of artificial intelligence system designed to understand and generate human language. The “large” part refers to both the massive amount of data it is trained on and the enormous number of parameters (internal numerical weights) it uses to learn patterns in that data. These models are trained on vast collections of books, articles, websites, and other text sources so they can learn grammar, facts, reasoning patterns, and even writing styles.

At its core, an LLM works by predicting what comes next in a sequence of text. If you give it a sentence like “The capital of France is…”, the model calculates which word is most likely to follow based on patterns it has learned during training. It doesn’t “know” the answer in the human sense. Instead, it has learned statistical relationships between words and concepts, and it uses those relationships to generate responses that are usually coherent and contextually appropriate.

The Evolution of the LLM

The first AI language models were introduced at the beginning of AI. The ELIZA model, for instance, is one of the first examples, debuted by MIT in 1966.

Today’s language models have evolved with the innovation of new technology. Modern LLMs use machine learning, NLP, and transformer neural networks (transformers) to understand and respond to human input. They also come in a variety of different styles, as we can see from some of the most popular examples of large language models produced in recent years.

Some common types of LLMs today include:

- Zero-shot models: Zero-shot LLMs are large, generalized models, trained on a massive, generic corpus of data. They can serve a variety of purposes, without the need for much additional training. GPT-3 is a common example of a zero-shot model.

- Fine-tuned models: Fine-tuned LLMs are smaller than their generic counterparts. One example is OpenAI’s “Codex”, a child of GPT-3 created for programming tasks. These tools are trained on precise data, and are used for specific tasks.

- Language representation models: Language representation models like BERT are designed to help computers understand the meaning of words. They’re intended for natural language processing and conversational AI purposes.

- Multimodal models: Multi-modal models build on the LLMs originally created to process text. For instance, GPT-4 can handle the input of both text and images, using computer image recognition to understand multiple media formats.

- Edge language models: Smaller than even fine-tuned LLMs, Edge models are highly precise solutions, which can run both offline, and on a specific device. They also offer greater privacy than some internet-bound counterparts because they don’t need to analyze data in the cloud.

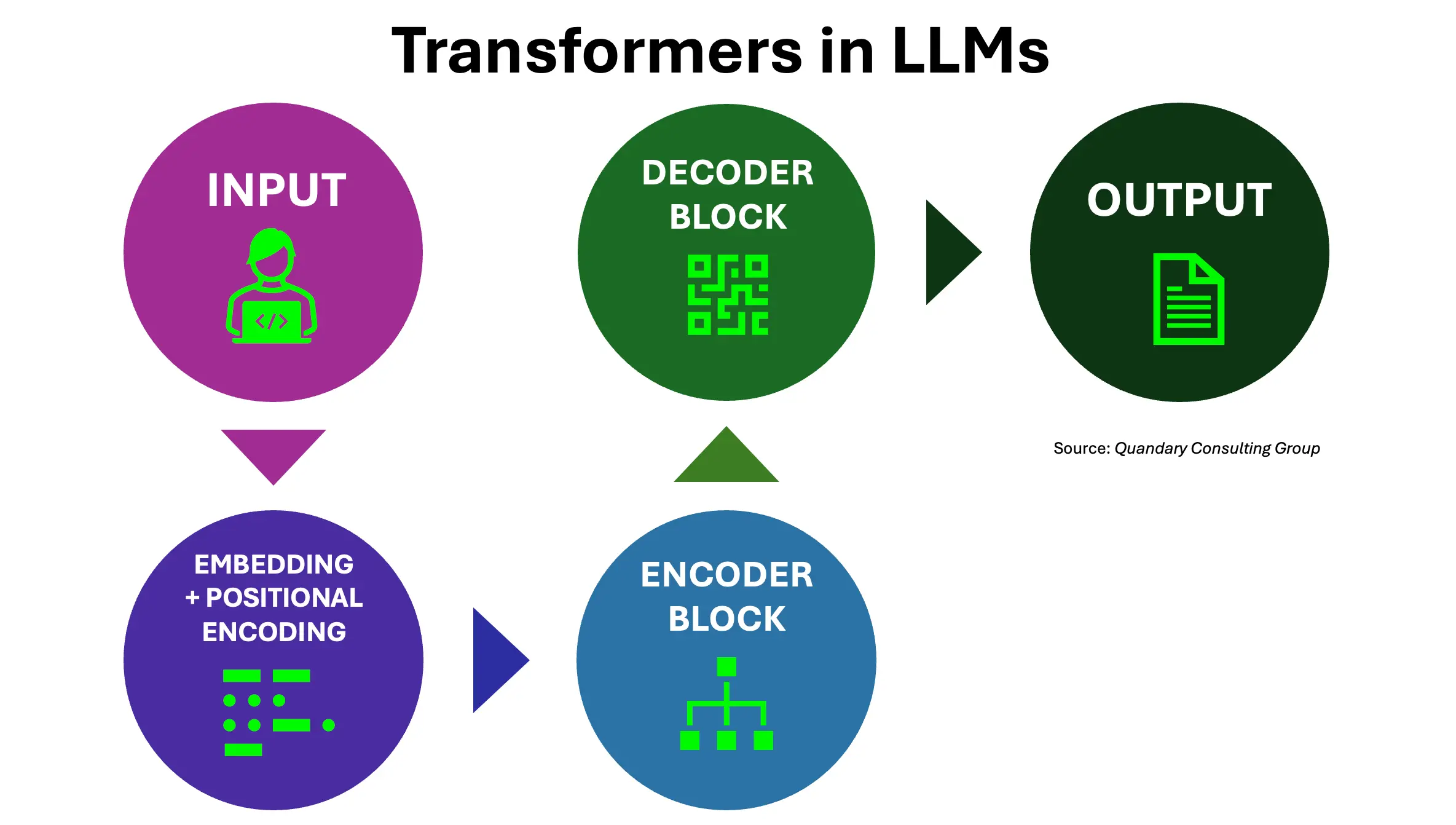

LLM Architecture: What is a Transformer?

Technically, most modern LLMs are built using a neural network architecture called a Transformer. Transformers rely heavily on a mechanism known as 'self-attention'.

Self-attention allows the model to examine all the words in a sentence at the same time and determine how strongly each word relates to the others. This is what enables the model to understand context. For example, in the sentence “The bank by the river was flooded,” the model can infer that “bank” refers to a riverbank rather than a financial institution because of the surrounding words.

Before the model can process text, the text is broken down into smaller units called tokens. These tokens are converted into numerical vectors (called embeddings), which represent meaning in a mathematical form. The model processes these vectors through many layers of neural computations.

Each layer refines the representation of the text, gradually building an understanding of context, relationships, and meaning. Finally, the model produces probabilities for what the next token should be, selects one, and repeats the process until the response is complete.

- Input Embeddings: Converting text into numerical vectors.

- Positional Encoding: Adding sequence/order information.

- Self-Attention: Understanding relationships between words in context.

- Feed-Forward Layers: Capturing complex patterns.

- Decoding: Generating responses step-by-step.

- Multi-Head Attention: Parallel reasoning over multiple relationships.

Variations of LLMs

Training an LLM typically happens in stages. First, there is pre-training, where the model learns general language patterns by predicting missing or next words across enormous datasets. After that, it often goes through fine-tuning, where it is trained on more specific data to improve performance on certain tasks or to behave more helpfully. Many modern systems also use reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF), where human reviewers rank model responses, and the model is adjusted to better align with human preferences for clarity, safety, and usefulness.

There are several different types of LLMs, and they can be categorized in a few meaningful ways. One common distinction is based on their architecture and training objective:

- Autoregressive (decoder-only) models predict text one token at a time and are especially strong at generating text. GPT-style models fall into this category. They are widely used for chatbots, content creation, and coding assistance.

- Encoder-only models (such as BERT) are designed primarily for understanding text rather than generating it. They process the entire input at once and are commonly used for tasks like sentiment analysis, classification, and information retrieval.

- Encoder-decoder models (such as T5 or BART) combine both approaches. They read the input text fully and then generate an output. These models are often used for translation, summarization, and structured transformations of text.

Another way to classify LLMs is by size. Models range from a few billion parameters to hundreds of billions (or even more when using mixture-of-experts techniques). Generally speaking, larger models tend to perform better on complex reasoning and language tasks, but they require far more computing power and are more expensive to run.

LLMs can also be categorized by accessibility. Some are open-source, meaning their weights and architecture are publicly available for researchers and companies to modify and deploy. Others are proprietary, accessible only through APIs or specific platforms. This distinction often affects how customizable and transparent the model is.

Despite their impressive capabilities, LLMs have limitations. They do not truly understand information in the human sense, and they can sometimes generate incorrect or fabricated responses (often called “hallucinations”). Their outputs are influenced heavily by how a question is phrased, and without access to real-time data, their knowledge is limited to what they were trained on.

In simple terms, an LLM is a highly advanced language prediction system trained at massive scale. By learning patterns in enormous amounts of text, it can generate responses that feel conversational, informative, and sometimes even creative. However, underneath that fluency is a system fundamentally driven by probabilities and pattern recognition rather than genuine understanding.

LLMs vs. Traditional Machine Learning?

Large Language Models (LLM) are built on machine learning principles, but they represent a major shift in both scale and capability compared to traditional machine learning systems.

Traditional machine learning models are typically designed for specific, narrowly defined tasks. For example, you might train one model to detect spam emails, another to predict housing prices, and another to classify medical images. These models usually rely heavily on structured data (like tables with columns and rows) and require carefully engineered features. A data scientist often spends significant time deciding which variables the model should pay attention to.

LLMs, by contrast, are designed to be general-purpose systems. Instead of being trained for one specific task, they are trained on massive amounts of unstructured text and learn broad patterns in language. Once trained, the same model can answer questions, summarize documents, write code, translate languages, and hold conversations — all without retraining for each task. This flexibility is a major departure from traditional machine learning.

Another key difference is scale. Traditional models may have thousands or millions of parameters. LLMs often have billions or even trillions of parameters. This scale allows them to capture far more complex relationships in data.

There is also a difference in how tasks are handled. In traditional machine learning, if you want a model to perform a new task, you typically retrain it with new labeled data. With LLMs, you can often achieve new behaviors simply by changing the prompt — no retraining required. This is sometimes called in-context learning.

Finally, traditional models usually require explicitly labeled training data. LLMs are largely pretrained in a self-supervised way, meaning they learn by predicting missing or next words in text rather than relying entirely on manually labeled datasets. This makes it possible to train them at enormous scale.

In short, traditional machine learning is task-specific and feature-engineered, while LLMs are large-scale, general-purpose, and capable of adapting through prompting rather than retraining.

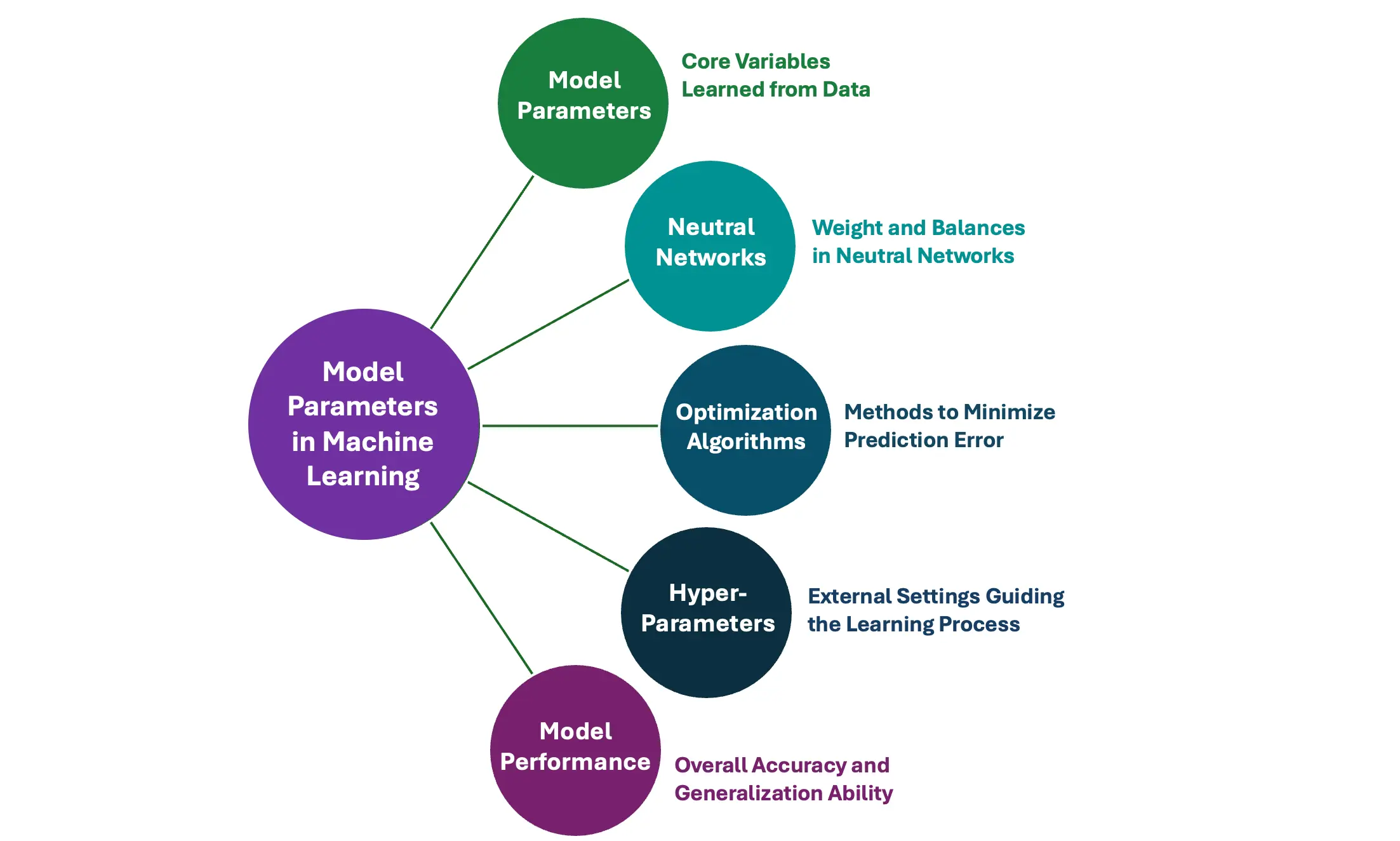

What Parameters Mean?

When people say a model has “100 billion parameters,” it can sound abstract. In practical terms, parameters are the internal numerical weights that the model adjusts during training.

Every time the model processes text, it performs mathematical operations on numbers. The parameters determine how strongly one word or concept influences another. You can think of parameters as the adjustable knobs inside the neural network. During training, the model tweaks those knobs to reduce prediction errors.

For example, suppose the model frequently sees the phrase “peanut butter and jelly.” Over time, its parameters adjust so that when it encounters “peanut butter and…,” it assigns a high probability to “jelly.” Those adjustments are encoded in its parameters.

More parameters generally mean the model has more capacity to learn subtle patterns and represent complex relationships. However, more parameters also mean:

- Higher computational cost

- More memory usage

- Greater energy consumption

- Increased training complexity

It is important to note that more parameters do not automatically guarantee better reasoning. Architecture design, data quality, and training methods also play critical roles.

In simple terms, parameters are the learned numerical values that store the model’s knowledge. They are not facts or rules written in plain language. Instead, they are distributed representations of patterns learned from data.

How Prompt Engineering Works?

Prompt engineering is the practice of designing inputs in a way that guides an LLM toward producing the desired output.

Because LLMs predict text based on patterns and probabilities, the way a question or instruction is phrased can significantly influence the response. The model does not “interpret” intent in a human sense; it reacts to patterns in the prompt. At a basic level, prompt engineering involves being clear and specific. For example:

- Vague prompt: “Explain AI.”

- More effective prompt: “Explain artificial intelligence in 300 words, written for a high school student, and include two real-world examples.”

The second prompt constrains length, audience, and structure, which helps shape the output. More advanced prompt engineering techniques include:

Role prompting:

- You can assign the model a role to influence tone and expertise.

- Example: “Act as a senior data scientist explaining this concept to a business executive.”

Few-shot prompting

- You provide examples of the desired format before asking the model to continue. This helps establish patterns the model can follow.

Chain-of-thought prompting

- You encourage the model to reason step-by-step by explicitly instructing it to show its reasoning process. This often improves performance on logical or mathematical tasks.

Structured constraints

- You can require output in JSON format, bullet points, or specific sections. This is widely used in production systems.

Context injection

- Providing relevant background information inside the prompt improves accuracy. For example, instead of asking a general legal question, you provide the exact contract text first.

- Prompt engineering works because LLMs are highly sensitive to context and pattern continuation. By shaping the context carefully, you influence which internal patterns activate.

In enterprise environments, prompt engineering often evolves into prompt design systems, where prompts are tested, version-controlled, and optimized for reliability and consistency.

LLMs Benefits

Large Language Models (LLMs) represent a shift in how humans interact with knowledge, work, and creativity. Rather than simply automating isolated tasks, they function as cognitive infrastructure — tools that augment thinking, accelerate execution, and expand what individuals and teams can produce; here’s a structured overview:

Productivity & Efficiency

- Automate repetitive tasks

- Drafting emails, reports, proposals

- Summarizing documents

- Generating meeting notes

- Faster research & synthesis

- Condense long materials into key insights

- Compare options or frameworks quickly

- Extract action items from complex content

- 24/7 availability

- Immediate responses without scheduling constraints

Knowledge Access & Decision Support

- On-demand expertise

- Explain complex topics in plain language

- Provide structured breakdowns of unfamiliar concepts

- Generate checklists and frameworks

- Better decision-making

- Scenario analysis

- Risk identification

- Pros/cons comparisons

Communication Enhancement

- Improved clarity

- Rewrite for tone (formal, persuasive, concise)

- Simplify technical content for non-technical audiences

- Translate between languages

- Consistency

- Standardized messaging across teams

- Style and voice alignment

Creativity & Ideation

- Idea generation

- Brainstorm marketing angles, product names, or campaign concepts

- Generate alternative solutions to problems

- Explore unconventional approaches

- Content creation

- Blog posts, social content, scripts, training materials

- Storytelling and narrative framing

Technical & Analytical Support

- Code assistance

- Write, debug, refactor code

- Explain error messages

- Generate documentation

- Data interpretation

- Analyze trends (when provided data)

- Generate insights from structured inputs

- Build models or formulas

Cost Reduction

- Reduce time spent on administrative work

- Lower dependency on external consultants for basic content tasks

- Scale support functions without proportional hiring

Personalization at Scale

- Tailored responses to different audiences

- Adaptive learning support

- Custom onboarding or training materials

Learning & Skill Development

- Step-by-step explanations

- Practice problems with feedback

- Simulated interviews or role-playing

Strategic Advantage (Enterprise Level)

- Knowledge augmentation for employees

- Faster innovation cycles

- Competitive differentiation through AI-enabled workflows

Important Caveat: Power Requires Judgment

While LLMs are remarkably capable, they are not authoritative sources of truth. They are probabilistic systems that generate responses based on patterns learned from vast amounts of data. This means they can produce outputs that are coherent, confident, and well-structured — yet factually incorrect. These inaccuracies, often referred to as “hallucinations,” occur because the model predicts what sounds right rather than verifying what is right. The fluency of the response can create a false sense of reliability, making critical evaluation essential.

For this reason, LLMs should not be treated as autonomous decision-makers, particularly in high-stakes environments such as legal, financial, medical, regulatory, or strategic contexts. They can assist with framing issues, surfacing considerations, drafting analysis, or organizing information — but final decisions require human accountability. Oversight is not optional; it is integral to responsible use.

Equally important, LLMs do not replace domain expertise. Experts bring contextual judgment, lived experience, ethical reasoning, and an understanding of nuance that extends beyond pattern recognition. They know when exceptions apply, when edge cases matter, and when a technically correct answer may be practically wrong. LLMs can augment that expertise — accelerating research, generating drafts, or challenging assumptions — but they cannot substitute for it.

In practice, the most effective model is not “AI versus human,” but “AI plus human.” LLMs expand cognitive bandwidth; humans provide discernment, validation, and responsibility. Organizations that recognize this balance are far more likely to capture value while mitigating risk.

LLMs Challenges

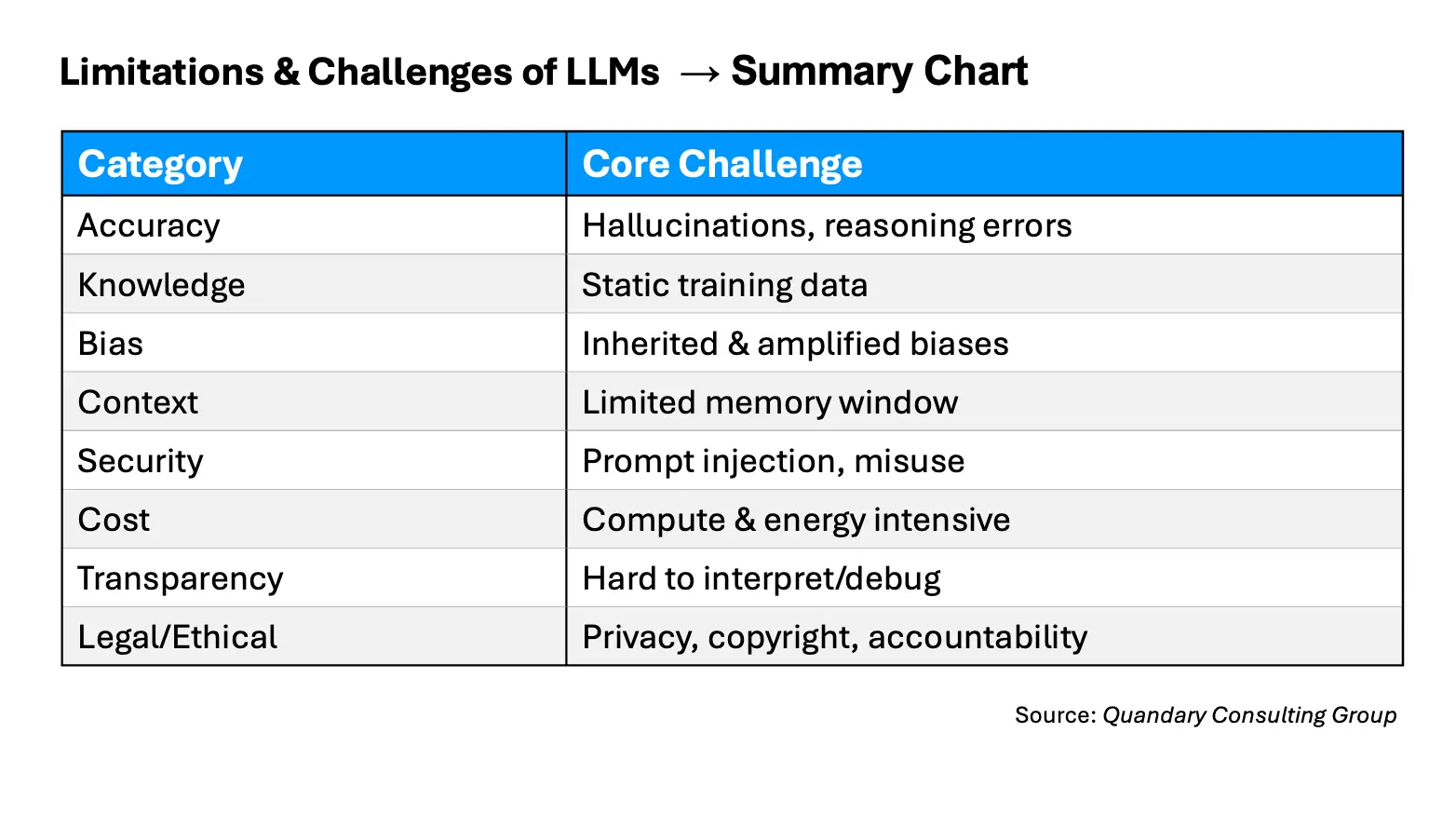

Large Language Models (LLMs) are powerful tools, but they come with significant limitations and challenges. These challenges span technical, ethical, operational, and societal dimensions.

Accuracy and Reliability

LLMs can generate highly fluent responses, but fluency does not guarantee correctness.

- They may produce hallucinations, meaning confident but factually incorrect or fabricated information.

- They can struggle with multi-step reasoning and complex logic.

- Their outputs can be inconsistent, sometimes contradicting earlier statements.

- Small changes in wording can significantly alter the response.

Knowledge and Understanding

LLMs do not truly understand information in a human sense. They generate responses based on patterns learned during training.

- Their knowledge is static, limited to their training data unless connected to external tools.

- They lack genuine comprehension, intention, or awareness.

- They may provide outdated or incomplete information.

Bias and Fairness

Because LLMs are trained on large-scale internet data, they can reflect patterns found in that data.

- They may inherit societal or cultural biases present in training sources.

- In some cases, they can amplify stereotypes or skewed perspectives.

- Ensuring fairness and neutrality remains an ongoing challenge.

Context and Memory Constraints

LLMs operate within technical limits that affect how much information they can process.

- They have a limited context window, meaning they can only consider a certain amount of text at once.

- They typically do not retain long-term memory across sessions unless specifically designed to do so.

- Important details may be overlooked if they fall outside the current context.

Security and Misuse Risks

The capabilities of LLMs create both operational and ethical concerns.

- They can be vulnerable to prompt injection attacks.

- Improper deployment may risk exposure of sensitive information.

- They may be misused to generate misinformation or support harmful activities.

Computational and Environmental Costs

Developing and operating LLMs requires substantial resources.

- Training large models demands significant computing power and financial investment.

- Inference at scale consumes considerable energy.

- Infrastructure costs can be high for enterprise deployment.

Interpretability and Governance

LLMs are often described as “black-box” systems.

- It is difficult to fully explain why a specific output was generated.

- Debugging errors can be challenging.

- Legal and ethical concerns remain around copyright, data privacy, accountability, and ownership of AI-generated content.

In summary, while LLMs provide remarkable capabilities, they are not flawless systems. Their limitations in accuracy, reasoning, bias, memory, security, cost, transparency, and governance must be carefully considered when deploying them in research, business, or public-facing environments.

Top 5 Company-Built LLMs

Here are five of the most influential company-developed LLM families:

GPT Series (OpenAI)

- The GPT (Generative Pre-trained Transformer) series is one of the most widely recognized and commercially adopted families of large language models. OpenAI introduced GPT in 2018, and each successive generation has significantly improved in scale, reasoning ability, multimodal capability, and reliability.

- The early versions (GPT-2 and GPT-3) demonstrated that simply scaling model size and training data could dramatically improve language performance. GPT-3, in particular, showed strong few-shot learning capabilities, meaning it could perform new tasks based only on instructions in the prompt rather than task-specific retraining.

- More recent generations (such as GPT-4 and beyond) introduced major advancements in:

- Improved reasoning and problem-solving

- Stronger coding capabilities

- Multimodal input processing (text + images)

- Larger context windows (handling longer documents)

- Better alignment with human intent

- A defining characteristic of the GPT series is its versatility. These models are designed as general-purpose systems that can power chatbots, enterprise automation tools, developer copilots, search augmentation systems, and content generation workflows.

- OpenAI has also invested heavily in alignment techniques such as reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF) and safety guardrails. This has made GPT models particularly suitable for enterprise integration, where reliability and risk mitigation are critical.

- From a business standpoint, the GPT family is primarily accessed through APIs and platform integrations rather than open-weight releases. This centralized deployment allows OpenAI to continuously update models without requiring users to retrain or redeploy infrastructure.

Claude (Anthropic)

- Claude is a family of models developed by Anthropic, a company founded by former OpenAI researchers with a strong emphasis on AI safety and alignment.

- Anthropic’s approach centers on what they call “Constitutional AI.” Rather than relying exclusively on human feedback during alignment, they embed a set of guiding principles (a “constitution”) that the model uses to critique and revise its own outputs during training. This approach aims to make the model more transparent, consistent, and resistant to harmful or misleading responses.

- Claude models are particularly known for:

- Strong long-context capabilities (handling very large documents)

- Measured, cautious response style

- High performance in reasoning and analysis tasks

- Enterprise-friendly safety posture

- One distinguishing feature of Claude models has been their ability to process extremely long context windows. This makes them especially useful for document-heavy environments such as legal analysis, policy review, and corporate knowledge management.

- Anthropic has positioned Claude strongly in enterprise markets, partnering with major technology firms and emphasizing reliability, safety research, and governance frameworks. Their brand identity leans heavily toward responsible AI deployment.

- In short, Claude models are built not just for performance, but for controllability and alignment at scale.

Gemini (Google DeepMind)

- Gemini is Google DeepMind’s flagship multimodal model family and represents the integration of Google Brain and DeepMind research efforts.

- Unlike earlier Google models that were primarily text-based (such as PaLM), Gemini was designed from the start as a natively multimodal system. This means it can process and reason across text, images, audio, and potentially video in a more unified way.

- Key strengths of Gemini include:

- Deep integration into Google’s ecosystem (Search, Workspace, Cloud)

- Strong multimodal reasoning

- Advanced coding and mathematical reasoning performance

- Large-scale infrastructure support from Google Cloud

- Because Google controls massive data infrastructure and consumer platforms, Gemini models are embedded directly into products like Gmail, Docs, Sheets, and Android systems. This tight ecosystem integration gives Google a distribution advantage.

- From a technical standpoint, Gemini benefits from Google’s long history in Transformer research (Google researchers originally introduced the Transformer architecture in 2017). It also leverages Google’s TPU hardware infrastructure for large-scale training efficiency.

- Gemini is positioned not just as a chatbot model, but as an integrated intelligence layer across consumer and enterprise software.

LLaMA (Meta)

- LLaMA (Large Language Model Meta AI) is Meta’s open-weight model family and has had enormous influence in the research and developer community.

- What makes LLaMA particularly important is not just its performance, but its accessibility. While Meta does not fully open-source everything, it has released model weights broadly enough to enable academic research, startups, and independent developers to experiment and build on top of them.

- The release of LLaMA significantly accelerated innovation in:

- Fine-tuned community models

- Domain-specific adaptations

- Lightweight deployments

- Research experimentation

- The LLaMA 2 and LLaMA 3 families improved significantly in reasoning, coding, and instruction-following performance. Meta has focused on making these models competitive with proprietary systems while allowing greater transparency and customization.

- A key advantage of LLaMA models is that organizations can run them on their own infrastructure. This is particularly important for:

- Data privacy requirements

- On-premise deployments

- Regulated industries

- Cost control

- Because the weights are accessible, LLaMA has become the backbone of many derivative models in the open ecosystem.

- In effect, LLaMA democratized access to high-quality large language models.

Mistral / Mixtral (Mistral AI)

- Mistral AI is a European AI company that has quickly gained attention for producing highly efficient and high-performing open-weight models.

- Mistral’s models stand out for architectural efficiency. Instead of relying purely on massive dense parameter scaling, some of their models (such as Mixtral) use a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture. In an MoE model, only a subset of the model’s parameters are activated for each token processed.

- This allows the model to achieve high effective capacity without the full computational cost of a dense model of equivalent size.

- Key characteristics include:

- Strong performance relative to parameter count

- Lower inference costs compared to similarly capable dense models

- Open-weight availability

- Efficient deployment on smaller infrastructure

- This efficiency has made Mistral models particularly attractive for startups and organizations that want high capability without frontier-scale budgets.

- Mistral has positioned itself as a serious open-weight competitor to larger U.S.-based labs, offering performance that rivals much larger models while maintaining flexibility for customization.

A Broader Perspective

Although all five model families are based on Transformer architectures, they differ in philosophy and positioning:

- OpenAI focuses on general-purpose performance and ecosystem integration.

- Anthropic emphasizes alignment, safety research, and enterprise trust.

- Google integrates AI deeply into consumer and enterprise infrastructure.

- Meta accelerates open research and community-driven innovation.

- Mistral prioritizes efficiency and open-weight performance optimization.

Each represents a different strategic interpretation of how large language models should evolve — centralized and API-driven, safety-first and controlled, ecosystem-embedded, open and customizable, or efficiency-optimized.

Final Perspective

LLMs represent a shift from narrow, task-specific machine learning systems to broad, adaptable intelligence systems trained at massive scale. Their power comes from billions of learned parameters, sophisticated architectures, and enormous datasets. Prompt engineering acts as the interface layer that allows humans to steer these systems without retraining them. Building an LLM at the company level requires deep expertise in data, infrastructure, distributed systems, and AI alignment.

While the technology is extraordinarily powerful, it is still fundamentally probabilistic pattern recognition — not true human understanding. That distinction is important, especially as more organizations integrate LLMs into critical workflows.

- By: Kevin Shuler

- Email: kevin@quandarycg.com

- Date: 01/03/2026

Resources

© 2026 Quandary Consulting Group. All Rights Reserved.

Privacy Policy